- Compendium of Historical Articles

- Rise & Development of MIL Music

- A Speech in London by Kipling

- The Romance of Regimental Marches

By Walter Wood, William Clowes and Sons, Limited, London: 94 Jermyn Street, 1932

Editor’s note: Due to the length of this article, I have added headings to aid in the navigation, as well as links, illustrations and videos for online purposes.

Introduction

There is no more inspiring and romantic music than British regimental marches. They represent love, conviviality, hunting, poaching, battles, victories, whims of military men and military men’s womenfolk and casual fancies.

Tunes by great composers and obscure musicians have been promiscuously annexed, and strange liberties have been taken with material that offered little hope of adaptation: even a solemn hymn tune has been turned into a regimental march. Generals and colonels have produced marches which have come down to own day, and several of the best marches in the British Army are creations of members of our royal families.

A regiment never dies, unless it is disbanded; it lives in the unbroken succession of its recruits, and with the regiment lives the quickstep.

When a regimental march is heard it may be a tune that has been played unbroken for generations or even centuries, as in the case of Dumbarton’s Drums, which has been the march of The Royal Scots for more than two hundred and fifty years; or you may be listening to march which was actually won in battle, like Ca Ira of The West Yorkshire Regiment.

Until very recent years nothing was done to ascertain how and why a certain tune was adopted and when any attempt was made it was by some enthusiastic officer or civilian. It is due to long and earnest research by such students that light has been shed in many dark places, and after long years of doubt and ignorance regiments have learnt something, if not all, relating to the marches.

Only a few regimental histories contain the story of the march; but now, as these stories become known, they are incorporated in the records, and there is hope that in time all regimental histories will include them. Doubtless also the Army List will add the name of its march to a regiment.

In recent years considerable improvements have been made in the compilation of the Army List, one of the most notable being the inclusion of the names of regimental marches. The titles of these periodicals are as interesting and significant as the names of many marches – for example, The Lion and the Rose (The King’s Own Royal Regiment), The Dragon (The Buffs), The Imps Magazine (The Lincolnshire Regiment), The Light Bob Gazette (The Somerset Light Infantry), The Wasp (The Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Regiment), The Green Tiger (The Leicestershire Regiment), The Oak Tree (The Cheshire Regiment) and The Covenanter (The Cameronians).

In the case of The Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry the name of the regimental march and that of the regimental journal are the same – One and All, which is the motto of the county of Cornwall; and this renowned regiment, the old 32nd-46th Foot, has the good fortune to know definitely the stories of both march and journal.

The obscurity of the origin of regimental marches generally is so great that until quite lately practically nothing was known of them either at the War Office or Kneller Hall. There has been, however, a marked growth in the interest in these fascinating compositions, especially by past and present officers of the regiments who realize the importance of learning, before it is too late, the circumstance of the adoption of a march.

Oral histories of regimental marches

When I first wrote upon the subject in the old Pall Mall Magazine I received letters from old officers in various parts of the world, either asking for or adding to information which I had collected; and at a much later stage the same result attended articles by me in The Strand Magazine and The Radio Times.

When I first wrote upon the subject in the old Pall Mall Magazine I received letters from old officers in various parts of the world, either asking for or adding to information which I had collected; and at a much later stage the same result attended articles by me in The Strand Magazine and The Radio Times.

A more definite result was noticeable in the case of my talks on regimental marches from the London studios of the British Broadcasting Corporation. Old soldiers of every rank who had had their memories stirred and revived by the descriptive matter and the music, wrote and helped me in some instances to trace the story of a march’s adoption. True, one or two of the tales made up in picture sequences what they obviously lacked in accuracy; but on the whole I obtained information which with reasonable care and foresight would have been officially available in past times.

These essential and elementary qualities were wanting in many Army officers of the old days. There were few serious men like Major George Simmons, of The Rifle Brigade, who in his wonderful letters told so much of the doings of the old 95th in the Peninsular War, and on his way to Dover to embark in May, 1809 wrote: “Our men are in high spirits, and we have a most excellent band of music and thirty bugle-horns, which through every country village strikes up the old tune Over the hills and far away.”

This quaint, heroic Yorkshireman in that sentence unconsciously gave a valuable idea of a regimental band and a regimental march of the period; and we shall see how fortunate The Rifle Brigade is concerning its famous march I’m Ninety-five.

Some of the old regimental marches are irrecoverable, but stories of them survive, and deepen our regret for their loss.

One story concerns that eccentric composer Samuel Welsey, who at the age of seven years was asked to compose a march for a Guards regiment – a circumstance which indicates that our own time has no monopoly of prodigies.

Samuel set to work, and produced a march of which it was said that it would probably inspire serene courage in the presence of the enemy. The critic was right, if Samuel was any guide, for the gifted juvenile was ‘carried’ by his father to a parade of the Guards to listen to his march.

The musicians, in happy unconsciousness of the composer’s presence, performed the music; whereupon the father asked Samuel if the music was to his liking.

“By no means,” answered Samuel.

The father then introduced Samuel to the band, which consisted, we are told of very tall and stout fellows.

“You have not done justice to my composition,” complained Samuel.

“Your composition!” exclaimed the astonished band.

“Yes, Mine!” retorted Samuel.

The band found breath enough to assure the aggrieved composer that they had correctly copied the score.

Samuel allowed that the bassoons and the hautboys were right; but he declared that the French horns were wrong.

The French horns to a man themselves against this attack, but Samuel demanded the production of the original score and ‘ordered’ the march to be played again.

The Guardsmen obeyed, and, wee assured, and can readily believe, submitted to Samuel with as much deference as they would have shown to Handel.

That notable march long ago fell into obscurity; but there is one which is greater still, and has been used by the Guards for many generations.

This is the march from Scipio, of which Dr. Burney wrote in 1772 that he remembered no other composition used in the Foot Guards, and in the marching regiments nothing but side-drums.

Tradition says that Handel specially composed this stately music as a parade slow march for The Grenadier Guards before it was introduced into Scipio.

Tradition, too declares that Handel composed The Buffs, the long cherished regimental march of The Buffs (East Kent Regiment)

Regiments & marches: a rich tradition

Some of our regiments are exceptionally rich in marches, and history and tradition concerning them, and there is none which in this respect has more distinction than the old 34th Foot, now the 1st Battalion The Border Regiment. To the fame of John Peel as the regimental march is added that of the unique honour of Arroyo dos Molinos, dating from 1811, when a French force in that Spanish town was surprised by the 34th. It is a remarkable fact that the British 34th cut off and captured the French 34th Regiment of the Line and made prisoners of a large number of officers. The Border Regiment alone in our Army beats the honour of Arroyo dos Molinos.

In that Peninsular battle, fought in a thick mist and violent storm of wind and rain, after forced marches, the 34th took the French 34th’s drums and drum-major’s staff, and with these at their head they came triumphant out of action.

That famous affair, forgotten by the world at large, is remembered in the regiment, and on October 28 in each year it is commemorated by ‘Trooping the French Drums’ by the full band and drums of the 1st Battalion.

The drums, four in number, are placed in the center of the square on which the whole battalion is drawn up in review order. The distant music of Le reve passé is heard, and soon the band and drums, in full dress, with the colours, join the parade. The colours are saluted and marched on, and then four drummer boys, dressed in the uniform worn by the 34th in 1811, and led by the smallest boy in the battalion, carrying the captured French staff advance in slow time to take over the French drums.

These old uniforms exact in every detail – pale yellow tunics, white knee breeches, black gaiters and shako – give a wonderfully realistic air to the ceremony, of which a great feature is that the drums, the brass of which is now wearing thin, are in charge of the boy drum-major.

The music of the regimental march of the French 34th was captured with the drums, and some of it is incorporated with John Peel, against which it is set in the introduction, so at this splendid ‘Trooping the French Drums’ there is heard a remarkable combination of marching tunes.

The French 34th were disbanded eight years ago. Both regiments were warm friends and for some years exchanged Christmas cards and cordial greetings.

Highland Regiments & Pipes

All Scottish regiments, Highland and Lowland, have marches which are chrematistic of their country, and are in a group by themselves. And it is a notable group, for it includes, in Dumbarton’s Drums, the oldest of our regimental marches, a tune which Pepys heard in the streets of Rochester in the year 1667. Other old tunes have been adapted as marches and they have been extensively used as auxiliaries to the official marches.

The Highland regiments are The Black Watch, The Seaforth, The Gordons, The Cameron, and The Argyll and Sutherlands Highlanders; the lowland regiments are The Royal Scots, The Scots Fusiliers, The Cameronians and The Highland Light Infantry.

The authorized quickstep for all Highland regiments is Highland Laddie, but before it was ordered for adoption many treasured tunes mostly played on the pipes, had been long in use, and no disposition was shown to abandon them in favour of a universal march, however good it might be.

It was, indeed, in some respects, a mistake to lay down a law respecting such a matter as a march, which is essentially an individual possession and Highland Laddie suffers from the same monotony as The British Grenadiers, which all Fusiliers regiments were compelled to use as the official march.

Both these old tunes are employed, according to order; but they are not so favoured as other marches which have entered into the possession of British regiments.

If all Scottish marches are excellent as music they are undoubtedly successful in their special purpose, and without exception they are cherished possessions. It would be as hopeless to expect a Scottish soldier to admit or confess any fault in his regimental march as it would be to suppose that a doting mother would allow any flaw in her beloved child.

The Londoner may be more or less unmoved as he listens to the music of the Guards band in the streets of the capital; but his pulse never fails to quicken when the pipes of The Scots Guards, now more splendid than ever in their feather bonnets, or the pipers of The Irish Guards begin their exhilarating playing.

He may not – in most cases does not – know what the bagpipes are saying, for only an expert can identify even a well-known tune; but he does realize the spirit of the instrument and of the achievement, and understands, however vaguely, the meaning of the ‘wild war notes’ which characterize such tunes as The Gathering of the Grahams, the rousing regimental march of the 2nd Battalion The Cameronians.

In this march, and others like Blue Bonnets over the Border, Cock of the North and The Campbells are comin’, the Scottish regiments have tunes which for marching purposes are unexcelled.

Highland regiments give an illustration of the saddling of a tune – Highland Laddie – upon a number of corps. This general application dates from 1881, and it was not appreciated by some of the independent Scottish military bodies.

The independence, yet loyalty, of that spirit is shown by the story of the Cameron who was at the head of the old 74th – The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders – in the early days of the regiment. The 79th were a single battalion regiment, a distinction which remained even long after 1881, when battalions were linked – and in some cases proved a most unhappy military marriage. There was a battalion over, and it was the 79th. To the end this unique isolation was greatly prized by the 79th, and there were many victories over those who tried to link the regiment with another.

A resolute effort was made to draft the 79th, to unite it with another corps; and amongst those who supported the movement was the Duke of York, Commander-in-Chief, son of George III. He told the colonel of the intention.

”Ye daurna draft us” declared the chief, indignantly.

“The king my father will certainly draft you,” returned the duke haughtily.

“Ye may tell the King your father, from me,” said the undaunted colonel, “that he may send the regiment to hell, if he likes, and I’ll go at the head of it – but he daurna draft us!”

And even His Majesty did not take the risk.

While resigned to the adoption, by order, of Highland Laddie, the Highland regiments clung to tunes which had become theirs by right of usage, so that to-day, while the official quickstep is always played, there are other tunes which are even more highly prized, because they have an individuality which the authorized march lacks.

These special marches are dealt with in their proper places, and it will be seen that, as in the case of The March of the Cameron Men, of the old 79th, they give something far more interesting and exhilarating than a set pattern composition.

Massed bands, mounted, & brass

The most impressive of all regimental marches are those which are played by the massed bands of The Brigade of Guards at trooping of the Colour on the Horse Guards Parade on the King’s birthday. Apart from the splendour of the spectacle, there is the excellent of the music and the variety of marches, slow and quick. It is in all respects a wonderful performance, for there are on parade five directors of music, 155 drummers, and instrumentalist bringing up the total of the bands to 250 men. Nothing is left undone to ensure perfect musical achievement. There is the Guards’ precision in marching, in slow and quick time; and long familiarity with the tunes. The stately slow marches offer a contrast with the march more animated quick march.

A further contrast is provided by the Household Cavalry band performances at the trooping ceremony. There is a magnificence of the state uniforms and the playing of such marches as Men of Harlech and the Keel Row. Mounted intrumentalists, with brass only and kettledrums, are at an obvious disadvantage compared with the infantry bandsmen, and in some ways cavalry marches suffer by contrast with infantry music. But sentiment and long association are powerful factors in retaining a tune which as music may not have much claim to admiration.

In the same class as trooping the colour is the Aldershot Tattoo, which provides some wonderful musical effects. There is marching and countermarching by the massed bands, drums and fifes, bugles and pipes of a score battalions; and the volume of sound adds vastly to the impressiveness of a uncommon spectacle.

No part of these displays is more appreciated than the regimental marches, not only by the onlookers but also the multitudes who by means of wireless can hear the tunes and will probably in the near future be able to see the actual ceremonies.

As to cavalry marches generally, the following remarks, offered in a communication to me by Mr. Francis J. Allsebrooke MM, bandmaster of the 17th/21st Lancers, are both interesting and enlightening: “The cavalry regiments all had their own slow march for the walk, the artillery the RA Slow March (a fine martial tune), and the RASC Wait for the Wagon. All mounted units used the same ‘trots’ for the trot past. These are The Keel Row, Monymusk and Anonymous. These trots were invariably played the commencing with No.1, The Keel Row and segue to Monymusk and Anonymous, thus running the three tunes into one, but with two bars of kettle-drum between each. The gallops commence with the Bonnets of Bonnie Dundee, The Irish Washerwoman, and another, the title of which I cannot remember for the moment. These were preceded by two-bar rolls on the kettle-drum (6/8 beating), with similar rolls between each gallop and change of tune.

Unofficial regimental marches have been taken into use in many ways, and one of the most interesting of these adoptions was through the kindness and helpfulness of Thomas Hardy, a lover of every good thing relating to Dorsetshire. In November, 1907, he was asked by the 2nd Battalion The Dorsetshire Regiment, then in India, if he could supply a marching tune with the necessary local affinity for use by the fifes and drums. He gladly complied with that request by sending out an old tune of his grandfather’s called The Dorchester Hornpipe, which he himself as a boy had fiddled at dances.

On reading of this incident in the Later Years of Thomas Hardy, I wrote to Mrs. Hardy, asking if she could give me any information about the air, and she most kindly answered: “I could find no trace of the old tune The Dorchester Hornpipe among the printed copies of music here. I did, however, find an old music book, over a hundred years old (one which belonged to my husband’s grandfather) and in this was the copied the tune – in m y husband’s writing. A friend copied this out for me, and I send it to you herewith.”

This short tune is lively and melodious, and a fit companion for the air which makes such an admirable march for the regiment – The Dorsetshire – whose name it bears.

The economics, personnel, & instrumentation of regimental bands

To-day, when regimental bands are established favourites with the public, and are of such all-round excellence, it seems strange that only a year or two before the Great War there was a proposal to abolish them for reasons of economy. It must be remembered that a considerable burden in maintenance fell on the private resources of the officers, not all of whom are able to meet such a call; but the proposal fell through, and today the regimental band is an established institution with the public, and is not so great a call on private funds as in the past. Broadcasting has proved a welcome source of revenue.

Regimental bands and regimental music owe much to the efforts of enthusiasts like the late Lieut. Colonel J. MacKenzie Rogan, formerly of The Coldstream Guards and Lieutenant J. Ord Hume. Colonel Rogan spent all his life in the atmosphere of regimental music. He was in the 11th Foot, now the Devonshire Regiment, as a band boy, and of these early days in the world of military music he wrote fully and with fascination in Fifty Years of Army Music.

In the late ‘sixties’, Colonel Rogan told, the composition of a depot band was curious. Flutes, drums and often bugles were massed together with the instruments ordinarily used, these instruments being played by old soldier bandsmen serving at the depot who had been invalided home from service battalions for change of climate. The programmes were usually made up of marches, overtures, mazurkas, operatic selections, quadrilles, polkas and gallops and the music was mostly written by foreigners, as so little by British composers was suitable. But, said Colonel Rogan, taking the bands as a whole in those days, and for many years afterwards, the standard of playing was as high as that of many military bands today, and perhaps higher.

The colonel of the 11th at that time, like many others, was a great believer in the foreign musician as director of a band. When Colonel Rogan joined the Army, about two-thirds of the bands where conducted by foreigners, mostly Germans; and all these foreigners were civilian who had no military training whatever and knew nothing of military life and discipline. They were, indeed, members of the itinerant German bands, which were are still so well remembered, and while some of them were excellent performers the great majority were ‘immigrant make-believers.’

The days of the foreign bandmasters, however, were numbered, and as the result of an Army Order issued in 1873 no more were engaged and British musicians came into their own and very soon proved their superiority. The status of the instrumentalists, too rose. Originally there were bandmasters-sergeants, then bandmasters, and at Colonel Rogans’ suggestion the title of Director of Music was given to those men who had been granted commissions. Today, in what are known as the ‘crack’ regiments, the Director of Music occupies the position which in most regiments is filled by the bandmaster, with warrant rank.

As a practical illustration of the progress of British Army music during the past century or so, Colonel Rogan said that fourteen old instruments, used in the eighteenth century, were borrowed from the collection of The Rev FW Galpin, Vicar of Halow. Some of these instruments were comical appearance, but they were put in working order, and the Royal Garrison Artillery band at Dover bravely undertook to play them. Ach selection was repeated by the full Coldstream band of sixty-six performers, and the contrast between the fourteen ancient instruments and the sixty-six modern ones was naturally very striking.

An equally practical illustration was given at the Royal Tournament in 1931, when The Royal Marines gave a display of pike drill with old English march music. The pike men were represented by men from the depot at Deal and the music supplied by the band and bugles of The Royal Marines. The display represented soldiers of ‘The Admiral’s Regiment’ in the uniform of 1664. The pike drill was taken from the Exercise of Foot 1690 and the colour carried in the arena was representation of the Major’s and the Company Colour of the period.

This interesting music consisted of a drum solo of the time of Charles I, and the full band marches were seventeenth-century airs Green Sleeves, Nottingham Ale, The Buff Coat has no fellow, and Joan’s Placket is Torn. The fife music was a march played in the Merchant Taylor’s Hall in 1638.

No attempt can be made, in such an introduction as this, to deal with the history of military music; but brief reference may be made to the subject. Music has been at al times associated with military bodies. The ancient Greeks favoured flutes, while the Romans preferred the trumpet. The fife, the trumpet and drum were the only purely military instruments used for a long period in our country. Military bands, as we know them today, developed from the family of instruments called cornetti, originally made from the horns of animals. The last member of this interesting family was the quaint serpent, so well beloved in country churches as well as in regiments; and it was played by Army bandsmen until about 1880, though its glory had long departed.

The serpent was used for the bass parts in military bands at the beginning of the nineteenth century. There is one that was played in the band of the Portsmouth Division of the Royal Marines until 1847. A serpent with fourteen keys due to the bell turned outward – an improvement due to the suggestion of the 46th Regiment (now the 2nd Battalion The Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry), and doubtless the performer on that contorted musical weapon was a source of admiration to a good many people, including himself.

In the days when negroes were included in our Army bands, the tambourine and a fantastic instrument called ‘Jingling Johnny Bells’ were in prime favour with the colour men, who were renown not so much for their musical abilities as their gorgeous uniforms and ambulant acrobatics. They flourished at a time when a regimental march was made up mostly of noise, a quality which they were singularly well able to supply.

“Jingling Johnny’ was carried on high, somewhat after the manner of a pastoral staff, and, judging from specimens which are still preserved, it was well shaken by the stable hands, producing sounds from its bells which obligingly amalgamated with any tune the band was playing.

Amongst other older instruments was key-bugle with six keys, which was used in the 1st Rifle Brigade shortly after the beginning of the nineteenth century. And a strange combination known as a bugle-horn was tested for eighteen months in the 2nd Life Guards. It was an attempt to form a bugle and trumpet into one instrument; and the alliance had the human infirmity of being a melancholy failure.

Drums and fifes are of great antiquity, and old records tell of ‘phifers or whifflers’. In 1810 and Englishman named Halliday, bandmaster of the Cavan Militia, invented the keyed bugle and afterwards chromatic instruments were rapidly adopted, and brought about what has been called the regeneration of military music. Other improvements followed – they were all shown in the Music Loan Collection at the Royal Military Exhibition at Chelsea in 1890. There were to be seen “drums of ancient form, with trumpets and bugles that have gained a well-earned discharge. The state silver kettle-drums and trumpets lent by Her Majesty the Queen will merit attention; and silver kettle-drums of earlier date are seen in those presented to the Royal Horse Guards by King George III. Did space but permit, pages might be filled in tracing the beautiful improvements in the wood wind, from the simple musette to the elaborate oboe of today, from the chalumeau to the clarinet and from the uncouth bombard of the fifteenth century to the rich bassoon of the present. Suffice it merely to point out how military music, in its infancy at the commencement of this century, has now grown to maturity. And that a great and eventful future lies before it time alone can show”

It is only forty-two years since that was written; and time has shown very clearly what excellence has been attained in military music – and there is no check to the advance.

The allusion to the silver kettle-drums and trumpet is a reminder of the magnificence of the state uniforms of the Household Troops. The most gorgeous of these, even in pre-war days cost ₤120 each.

The British regimental bandsman today must be prepared for any musical emergency. He never knows what surprises and Army Order may spring upon him, nor what strange call may be made upon his professional skill. From Army Orders for April 1930, he learned that “a new Chinese national anthem has now been published. All hands should be in possession of at least one set of music.” So that whenever a Chinese state occasion arose the anthem should be available for performance.

It was observed at the time that the Army bandsman considered himself fortunate in not having to sing, as well as play, the anthem of which even the Chinese Legation in London knew only it existed. It was the song of the Chinese Nationalist Party, China’s latest Government. The music was sent to Kneller Hall and was arranged for playing by British military bands. It is at any rate a bizarre addition to our extensive military musical resources.

Such and Order is a reminder that amongst our unofficial regimental marches is a Pathan tune, Zachmi Dil of which the story is told in the note on the King’s Regiment (Liverpool).

Army and Navy Regimental Marches

Regimental marches can be definitely grouped, and in grouping and analyzing them the mentality of military men of the past when dealing with music is clearly shown. With a few exceptions their choice was for something easy and capable of being played on simple instruments by musicians who were not too highly trained.

It must be remembered that until recent years there was no school of military music at Kneller Hall, and that there was not the long, skilled and careful training of bandmasters and bandsmen which is now imperative; nor the fine instruments which are available today. And there were public performances of music which would not now to tolerated.

On November 10, 1829, The Times, describing the Lord Mayor’s Dinner at the Guildhall said “Gog and Magog, we thought, looked more serious and thoughtful than usual… but that might have resulted from their being not a little ashamed of the miserable choristers, who every now and then annoyed the company with what they called singing. These gentlemen chanted as independently of each other as if they had not been hired to sing together, which, however, was doubtless their engagement.”

In the earlier days of organized music in the Army the principal thing to aim at was noise, a martial noise; and much dependence was placed on the drums, especially in ‘marching’ – foot regiments. The drums and fifes were the principal instruments in use and even when they were reinforced with bugles, horns, and hautboys the result was not, from the standpoint of today, satisfactory. But the means were adopted to the ends, and crude music was in keeping with crude times. It was enough marching troops were cheered and encouraged and a brave show made when passing through a town or village; and for such purposes tunes like The British Grenadier and Over the Hills and Far Away served quite effectively.

A definite step in connection with naval marches was taken early in 1927, when Admiralty Fleet Orders gave a number of airs which had been approved for playing, on authorized occasions, by naval and Royal Marine bands. Old favourites had an addition in music from Iolanthe as a general salute for British flag officers who were not entitled to Rule Britannia. The general salute for governors, high commissionaires, etc, British general officers and air officers, foreign officers and officials was The Garb of Old Gaul; the march past of the Royal Navy was Heart of Oak; that for Royal Marines was A Life on the Ocean Wave and Nancy Lee was used for he advance in review order.

In those Fleet Orders the old mistake of Hearts of Oak was made. The title of the song is Heart of Oak, the words being by Garrick who wrote – Heart of Oak are our ships, Heart of Oak are our men – meaning, of course, the heart of the oak, the toughest and soundest part of the tree. The verses have no great merit, indeed they are no better than most of the jingo productions of their day. They are forgotten; but the tune which was composed by Dr. William Boyce, who died in 1779, interprets the contemporary patriotism and keeps his name is in greater remembrance than his much more serious work relating to English cathedral music. Heart of Oak is an admirable quickstep and specially interesting because of its age.

A Life on the Ocean Wave has been played as march for many years. It was authorized for use by the Royal Marine Light Infantry and now that The Royal Marines include both artillery and infantry, the tune serves the purposes of both. Nancy Lee is also a well-established march. It is the work of FE Weatherley, who wrote the words and ‘Stephen Adams’ who composed the music. The real name of Adams was Michael Maybrick and some of his compositions attained an extraordinary popularity. Amongst these success was Nancy Lee and so great was the craze for it that Punch published a drawing by Du Maurier showing ten young baritones turning up at an evening party, each armed with a copy of the song.

Great advances are being made in naval marches and a notable illustration of this progress was afforded in September 1929, when H.M.S. Shropshire commissioned at Chatham. On the 20th of that month it was announced on board that the Shropshire Society in London was to visit the ship on the following Saturday, to present silver plate to the ship; and in honour of the occasion the song of the Society, All Friends Round the Wrekin, was to be sung. This song was first scored for military band, then orchestra, then for singing.

Two days before the gathering on board, the captain of the ship, Captain RW Oldham RN made the admirable suggestion that as a special compliment the song should be arranged as a march and played by the band to march the ship’s company to the quarter-deck for the ceremony. This came as a great and delightful surprise to the Society and the ships’ company and a letter was afterwards received from Sir Edward German complimenting Bandmaster Upstell, who was the bandmaster of the Shropshire, on his arrangement. This instance, from the Royal Navy, is an excellent example of the coming into being of an essentially regimental march.

At the beginning of this century instructions were given for The Boys of the Old Brigade to be adopted as the marching past music for all battalions of the Royal Reserve Regiments which then existed; and this very popular and stirring tune was played in quick time when the Royal Guards Reserve Regiment marched past at trooping the colour on Queen Victoria’s last birthday.

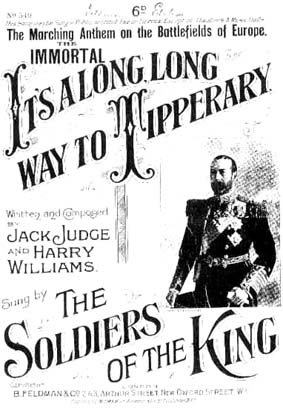

So far no such official use has been made of any of the tunes that were used as marches during the War, though some of them are imperishably connected with it. Most famous of them all is Tipperary and perhaps steps will be taken to preserve its memory in the Army. The question of musical quality can scarcely arise; sentiment is the deciding factor. Already Tipperary is specially identified with Armistice Night; but of the thousands who join in singing it, few indeed could say who the author is or whether he is living or dead. His name was Henry James Williams and he died at the age of fifty years on February 21, 1924. He was cripple, unmarried and lived with his parents at the Plough Inn, Temple Balsall, Warwickshire. In the little cemetery of Balsall a marble stone shows his resting place, the inscription reading:

Author of

“It’s a long, Long Way to Tipperary.”

“Give me the making of the songs of a nation, and let who will make its laws.”

The year 1922 became memorable in our military history because during that period five Irish regiments were disbanded – The Royal Irish, The Connaught Rangers, The Leinster, The Royal Munster Fusiliers and The Royal Dublin Fusiliers; and with them went that splendid body The Royal Irish Constabulary. The names of the regiments are still given in the Army List, ghostly reminders of many loyal and gallant bands. It is fitting enough that some reference should be made to their marches and for this purpose some of the regiments have been resurrected in their rightful place in this book.

Nor can the R.I.C be allowed to pass from remembrance, for they had their admirable band and their quickstep – that delightful Irish tune The Young May Moon. The .I.C. band, both military and string, had the reputation of being one of the best in existence, ranking with such bodies as the band of the “Blue” Marines. It enjoyed the benefit of long service and permanent barracks. At one time its cornet soloist, Sergeant Shelton, was unrivalled, and both he and the band in general were in great request for public and other functions.

That was then, this is now

There is little hope of learning why and when many of our regimental marches were adopted. We have to be satisfied with the fact that a certain quickstep is associated with a certain regiment; but a necessary lesson has been learnt from past neglect in recording the circumstances of adoption.

In these days with the greater care that is taken of records, the keenness of officers to ensure for their successors better regimental means of information and the selection of new tunes as new units are formed, there is assurance that the reason for choosing a certain tune has not been overlooked.

So we are able to know definitely why and when some the latest marches were adopted and get the reliable stories of the origin of such quicksteps as Wings of the Corps of Royal Engineers; The Rising of the Lark of the Welsh Guards; The Village Blacksmith of The Royal Army Ordnance Corps; Bonny Nell of the Royal Army Medical Corps; Begone Dull Care of the Royal Corps of Signals; and the Royal Air Force March of the Royal Air Force.

These stories are interesting enough even to contemporaries; they will be infinitely more so to posterity and especially if, as all now hope and pray, the marches may be , not incentives to the military spirit, but romantic reminders of what brave enduring men of old did and suffered for their fellows.